(This short story was written in aid of World Suicide Prevention Day which takes place each year on 10th September. So I’m a little late. I apologise if this story upsets anyone but it doesn’t belong to me, it belongs to the *fictional* character)

Méabh smoothed out her silk olive green shirt. It looked baggier on her now, just as she had originally intended it to look when she first bought it. Her silver pendant, with two little pictures of the kids inside, hung loosely around her neck, giving her a look of carefree sophistication. She tousled her hair with her right hand, noting that the persistent greys were more prominent than usual. When was the last time she’d dyed it? She couldn’t remember. This inability to remember things, to retain basic pieces of information was starting to grate on Méabh. Once she had prided herself on being unnaturally organised, taking the jibes from Niamh and Diarmuid as good old-fashioned banter. Now, she felt that things were slipping away from her, but she couldn’t articulate what these things were. Time, her memory, her sanity? She tugged the skin on her face towards her cheekbones. This is what I look like now, she thought, an old turkey with excess skin like a sucked-out stomach after liposuction. That’s how she felt too: sucked out, hollowed, empty.

She threw the dishevelled duvet over the king-sized double bed, Conor’s suggestion of course. What an idiot I was, she thought, smoothing over the corners, just like she felt she was constantly smoothing over their marriage. They’d bought it a few years before she’d began sleeping in the spare room, when the children were still small. She had thought that such an extravagant purchase was a statement of where they were in the world, a sign that their marriage could be rescued. It was certainly a far cry from the old, springy mattress she’d slept on as a child, turning and readjusting so that the springs didn’t rub against her ribs. Conor had promised her that she would never be so neglected again, that she would always have food and a roof over her head. And she strove to be a better mother than her own mum ever was.

Nobody could dare accuse Méabh of being anything less than a wonderful, doting mum. It was well- known among the locals of Tullamore how incredibly organised and talented she was: she had always donated baked goodies to the kids’ school cake sales made from scratch; she had presided over the Parent’s council in Tullamore College for seven consecutive years; for sixteen years she ferried the kids to their after-school activities day after day, and was never without a kind word and a warm smile for those she met on the way. Whenever she spoke of Niamh and Diarmuid, her heart seemed to swell with pride. Diarmuid had just a few weeks before moved up to Dublin to be with his big sister in UCD. She was studying Arts while her brother wanted to be a doctor, just like his father. Indeed, he was becoming increasingly like his father, reflected Méabh: cold, arrogant and unfeeling.

Now that the children had flown the nest, the grim reality of how toxic their marriage had become was truly beginning to take hold. Conor had never been cruel to her in front of the children: distant, certainly, but until lately he had never descended to the depths of calling her names, putting her down, criticising her ironing, her cleaning efforts, her cooking. Perhaps, reflected Meabh, that was owing to the fact that there was always the children to act as a buffer between them. She hated herself for putting them in that position, and became disheartened often by how easily they had accepted it. Just like her Sunday roast dinners with the gravy made from scratch, watching her children referee between her and Conor had become a part of their lives.

At precisely five to eleven, the letterbox jangled. She heard the heavy thud onto the mat in the hall. Another pile of final notices, no doubt. Lately her post seemed to come in clumps, a collection of demanding letters and legal threats. For a moment, Méabh allowed herself to fill with self-pity. This is not how I imagined life at fifty, she thought, rubbing her temples. She’d hoped for a career of her own, something in fashion perhaps, something that would solidify her purpose. Now that the kids were gone and her marriage was on the rocks, she felt deprived of the opportunity to make her own identity. But she was just doing what women did at that time: she raised the children while Conor focused on his career. She hadn’t resented him for it, then.

She sat on the bed, staring into space, hoping to hypnotise herself into some kind of mental paralysis. Her heart was racing, as if she was about to get caught doing something wrong, as if someone would burst through her bedroom door and unmask her as the imposter that she knew deep down she was. Using the palms of her hands, she pushed herself upwards, feeling her cold blood rush to her feet. She didn’t have time to sit around moping. Those buns would not bring themselves to the school coffee morning.

Few things lifted Méabh’s spirits these days like seeing her pristine kitchen glow in the orange September light. The light shone from the marbled grey countertops and the black presses were immaculately clean. Méabh was proud that, at first glance, no-one would be able to tell from looking at her kitchen that she was a keen baker. Once she had all the ingredients organised, she loved to bake: to feel the flour clumping between her fingers, to watch the eggs, butter and sugar creaming in the mixer. The tubberware box in the corner of the counter was the reward for her efforts. Everyone always complimented her on her buns, her cooking. In fact, it seemed that everyone in Tullamore was envious of her full stop. Meabh acknowledged this without arrogance. She knew that her address of Clonminch Road was not merely her home but a status symbol, a statement about her place in life. Once she and Conor separated, where would she end up? What would her new address say about her?

Finally, she grabbed the keys to the Merc and trotted out of the house, wearing her shiny black high heels. She hopped into the car, carefully placing the box beside her on the seat. For a second, she stared into space, trying to remember why she was in the car. The kids probably wouldn’t have approved of her continuing to support school activities but, as she reflected, at least they were not here to suffer the embarrassment of her. Suddenly, her heart froze. Had Niamh really not been home for a whole weekend since the beginning of May, four months beforehand? Meabh was saddened by this realisation, but she knew why. In fact, she and her daughter had only spoke about it two weeks ago.

‘I don’t live there anymore, mam,’ Niamh had said on the phone, ‘so there’s no point in me coming home. Anyway, it doesn’t feel like home, you know what I mean?’ Niamh’s honesty had shaken her. Meabh had always thought that whatever was going on between her and Conor, she had always ensured that the kids felt secure and loved. She also hadn’t bargained for how much she’d miss her only daughter and their cups of hot chocolate in front of the Late Late Show every Friday night, going shopping in Athlone on Saturday afternoons, going for dinner in the Court every Sunday. Once, she had even seen Niamh not only as her daughter but her best friend. Alas, Méabh had let her down somehow. Niamh came from a different generation, Meabh reflected; she didn’t need the approval of a man or any kind of partner to justify her existence. That’s where I went wrong, she thought as she started the car.

As she pulled into the parking space, Meabh felt ashamed. I’ve no right to be here, she thought, watching the other mums walk in together, laughing and smiling. She envied how carefree they all seemed to be, some of them even wearing long shapeless t-shirts and plimsolls. Regina Hogan always came to these events in her tracksuit bottoms, the grey one with the red paint down the left leg. It annoyed Meabh that she never made an effort; some days, the woman barely looked presentable. And yet, Meabh noticed, Regina seemed happy. In fact, she was everywhere: at fundraisers, community events, sponsored walks. She waved as Meabh got out of the car, revealing a wet patch of sweat under her arm.

‘Well, pet,’ she drawled as Meabh walked towards her. ‘Aren’t you very good to take time out of your busy schedule and come up here with us commoners, eh? They look gorgeous,’ she said, opening the box in Meabh’s hands, then leant in closer to her, releasing a raspy laugh. ‘I bought mine in Flynn’s this morning. Was never one for this baking lark.’

‘No.’

‘Not for me. I’m an ‘ater, not a baker. We can’t all be as talented as you!’

Méabh was becoming irritated now. ‘I wonder how many will turn up,’ she said, quickening her pace, her high heels clacking behind her. The smell of old gym sweat, of cheap deodorant and cheese and onion crisps hit her as she opened the door, holding it open for Regina.

‘Thanks, pet,’ Regina smiled at her, flashing her yellow- brown teeth. ‘By the way, haven’t seen you working in the shop for a while. You still there?’

‘No.’ Méabh was tired. ‘Ah, it was just something to get me out of the house now that the kids are gone. Turns out I have plenty to keep me occupied!’ She held up the buns as Regina smiled and walked down the corridor towards the gym. It surprised her that Regina had noticed that she was not working in Centra anymore. Did anyone else notice, she wondered?

She wished she had the courage to tell people the real reason: that up until a few weeks ago, Méabh had spent the majority of every day in her pyjamas. That she had found every single task to be physically exhausting, from brushing her teeth to making a cup of tea. Conor had been gone for a month on one of his so-called business trips to Dubai, but Méabh wasn’t stupid. She knew that there was another woman involved, and that there had been for a long time. When she was in the house, alone, there didn’t seem any point in cleaning, cooking proper meals; mostly she’d lived on beans on toast or micro meals. It wasn’t her usual style: Meabh had once been a great believer in the benefits of healthy eating.

Frightened that she was starting to lose her mind, Meabh had gone to the doctor two days beforehand. She knew she wasn’t right: she’d even had two cigarettes the day before, despite not having smoked in nearly thirty years. It had killed her to confess that to the doctor.

I don’t feel like myself at all, she’d said.

Dr Murphy rubbed his head with his pen. You were fifty last week, yes?

Meabh had been insulted. I don’t think that’s relevant, Doctor.

Perhaps it’s all part of the menopause, he said, looking blankly at the screen in front of him. You ever been on Prozac, or Valium? It might help. Do you feel anxious? Meabh conceded that she did, that as long as she could remember, she had always been what her mother called ‘highly strung’.

Calm down, he’d said to her. Try some mindfulness or meditation. There’s apps for everything these days. He wrote her a script for Valium and held it out to her.

One more thing, he said, still distracted by the computer. Have you ever had unwanted thoughts? Méabh had frozen, feeling as if Dr Murphy had caught her unaware in complete nakedness. She felt invaded, exposed.

No, she’d replied, giving a small laugh at the absurdity of the idea, then, as an attempt to inject some humour into the tenseness, she added: Don’t worry, I love myself too much to do away with myself! She’d snatched the prescription off the table, not looking back as she’d walked out, holding her head high.

Now, Méabh sat in the car, watching the windscreen wipers move back and forth, squeaking slightly as they rubbed against the window. Squeak swish, squeak swish. This noise, she reflected, represented where she was right now: just going back and forth, going through the motions but not actually going anywhere. She was tired from her efforts of making polite conversation with other parents when really what she had wanted to do was crawl back into bed. The rain pelted loudly against her window, demanding to be let in. The six foot walk to her front door seemed impossible, then. If she got up, walked over and turned the key, she would then have to make dinner. Then she would have to clean up after and be in bed before he came in. And she would be doing this same thing, over and over, until they separated and she ended up in a grotty little bedsit on Church Street. That was assuming she could afford the rent and bills, of course, not to mention the bills that were waiting for her now, neatly stacked on the pristine counter.

Méabh’s entire body felt heavy.

This is it, she said. I cannot do this anymore.

She turned on the radio in anticipation of having to drown out the floods of tears that she wished she could cry. Still she felt nothing. Not sadness, not anger: nothing. She opened the box of Valium and took one, and told herself she felt better. Then she took another, and another. The loud radio hummed around her, like a choral chorus, hemming her in:

…and it’s not a cry, that you hear at night;

It’s not someone who’s seen the light,

It’s a cold and it’s a broken halleluiah….

The music became increasingly muffled. Then, silence, the silence she’d been looking for. Diarmuid would find her slouched over the steering wheel, her silver pendant broken and the two kids grinning up at her from her lap. In these photos, they would never get older, and neither would she.

Absolutely shocking, they would say, later, after the news broke. She had so much going for her. Those beautiful children, God love them.

How’s Diarmuid going to cope now? Sure a couple more suited to each other I’d never seen!

…and she was so talented and all, ah wasn’t she just a lady?

Now Ann Kelly told me the other day she thought she might’ve got fired from that shop that she was working at…

Sure what is this town coming to, everyone killing themselves, what is the story?

Méabh would soon be yesterday’s news, and her neighbours would go on as before: smiling at each other, giving a friendly wave, or avoiding each other’s gaze, hoping nobody would ever discover their pain. All they had now was pointless speculation, and a ‘For Sale’ sign where she used to live.

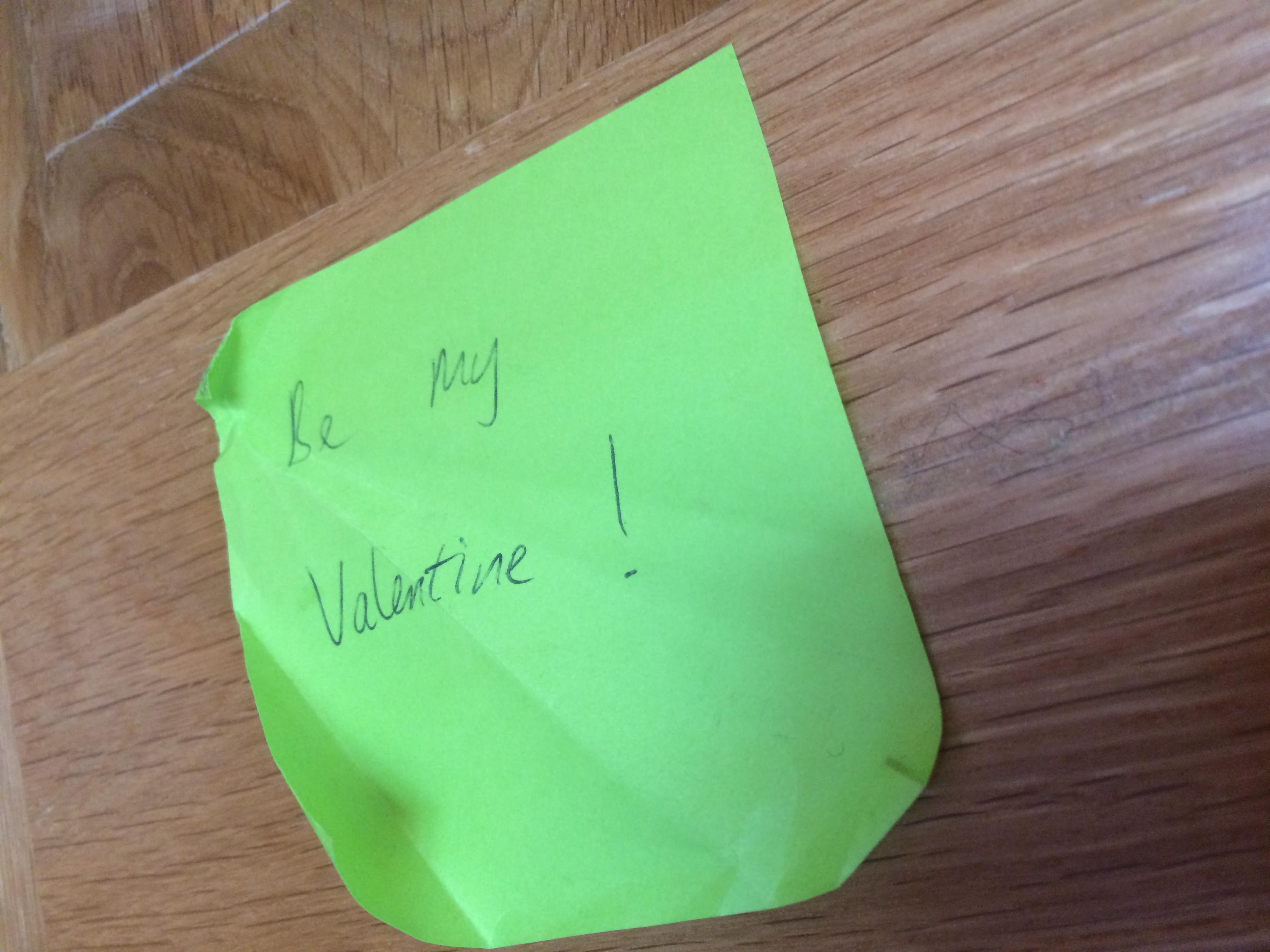

A Valentine’s love post-it from about six years ago my husband left for me on the inside of a press so I’d see it when I opened the cupboard to make my breakfast. It’s still there!

A Valentine’s love post-it from about six years ago my husband left for me on the inside of a press so I’d see it when I opened the cupboard to make my breakfast. It’s still there!